If you were to

take the story of Cinderella and replace the fairy godmother with

grace, the goings-on with the pumpkin and mice with actual miracles,

and the prince with

Christ, you'd have the story of St. Germaine Cousin.1

Germaine was born in 1579, in a little hamlet near the town of Pibrac,

in the Languedoc-Gascony area of southwestern France that is now known

as the Haute-Garonne. To find it on a map, know that Pibrac is a little

over 9 miles west of Toulouse, the city in which St. Dominic founded

the Dominican Order and received the rosary

from the Blessed Virgin.

From the very beginning, Germaine's life was marked by suffering: she

was born with a deformed, practically useless hand, and, very

early on, came down with "the king's evil" -- scrofula, a disease that

causes swelling of the lymph glands, especially in the neck.2

Untreated with antibiotics, these swellings can become abcessed,

oozing, and painful. To compound her miseries, her mother died when she

was very, very young.

And then things got even worse: her father married a woman who had

daughters of her own, girls she much favored over Germaine, whom she

treated with contempt. Using the

excuse of keeping her girls safe from scrofula, she moved Germaine from

the house to the attached stable and put her to work as a shepherdess

and spinner of wool at a very young age. Imagine

living in what amounts to a barn, without even fire for warmth

during winter, and then being made to spin yarn with icy-cold hands,

one of which was mostly paralyzed! Even Cinderella had a fireplace to

warm herself by!

Germaine never had shoes, and was given only old, tattered clothing to

wear. In addition to these humiliations was physical abuse, with her

stepmother once even pouring boiling water on her legs in anger.

Why Germaine's father allowed this nightmarish situation is unknown;

people have

wondered if perhaps Germaine had actually been a foundling -- unwanted

and abandoned at the Cousins's doorstep -- or if, maybe, she wasn't

biologically related to her father, but was a daughter his wife had

from a previous marriage. Perhaps one of these things is true, but

nothing excuses the way Germaine was treated.

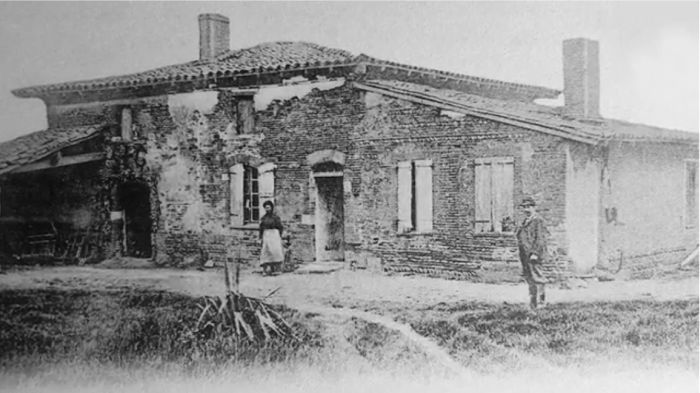

The home

of St. Germaine. The door on the left is the entry to the stable, where

the animals and St. Germaine lived.

The home

of St. Germaine. The door on the left is the entry to the stable, where

the animals and St. Germaine lived.

The door on the right is the entry to the house proper.

Sickly, frail, thin, separated from family life, and with only God, His

Saints, the angels, and her sheep for friends, Germaine didn't allow

the abuses she suffered to cause her to become bitter and resentful;

quite the opposite. She became a paragon of piety, so much so that

villagers would mock her for it -- yet another source of torment.

But she persisted in honoring God with all her might and with what

little she had. She fashioned a rosary out of the yarn she made and

would pray it often in the fields or at night in her makeshift bed

under the stairs in the stable. She would fall on her knees when she

heard the Angelus bells ring three times

each day, and would do so even if she were standing in water -- which

would not be infrequently since she attended Mass every day and had to

cross a stream to get there. She would walk with her sheep to the 13th

century parish church named for St. Mary Magdelen and,

though the area was forested and filled with wolves, she'd fix her

shepherdess staff into the ground and trust God with the care of her

lambs while she attended Mass. And no harm ever came to them; not a one

was lost.

L'Eglise Sainte-Marie Madeleine, St.

Germaine's parish church

One day, after much rain, the stream that ran between her home and her

church became swollen and raging, but she walked serenely to its edge,

made the sign of the cross, and entered in,

only to have the waters part, like the Red Sea did for Moses, so she

could cross without drowning or even getting wet. This was witnessed by

villagers who then began to regard her with a newfound respect --

perhaps even awe.

But she carried on as always, with the most profound sense of God's

Presence. So humble was she that, in spite of abuses that would cause

most to suffer from a burning sense of resentment and desire for

revenge, her prayer was, simply, "Dear God, please don't let me be too

hungry or too thirsty. Help me to please my mother. And help me to

please You."

She would even give what very little she had to beggars. Once, in an

event which echoes a story from the life of St. Elizabeth of Hungary,

she wrapped bread in her apron to take to the poor, but was

stopped by her stepmother who accused her of stealing the food. She

threatened to beat Germaine, and was hurling abuses at her when two

villagers intervened to protect the girl. The stepmother again accused

her of theft and ordered her to open her apron and show what it

contained -- and when she did, beautiful flowers spilled out.

After years of neglect, her father came to repent of the abuse his

daughter endured.

Realizing the evils that had been committed against her, he invited

Germaine back into

the house, but she declined the offer, telling him that she was

content among the animals.

Thus she lived her life alone -- quietly, humbly, and full of love for

God and neighbor as Lord Christ commands and as St. Matthew records in

chapter 22 of his Gospel:

Master, which is

the greatest commandment in the law?

Jesus said to him: Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole

heart, and with thy whole soul, and with thy whole mind. This is the

greatest and the first commandment. And the second is like to this:

Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.

And then, in 1601, God took her home -- but not, so the story goes,

without granting to the world another sign that St. Germaine is someone

to emulate and take as a friend: on the night of her death, two monks

who were on their way to Pibrac saw young girls in white and surrounded

by a golden light descend from the skies and then walk toward the

Cousins' house. Then, a bit later, they saw the girls again -- this

time accompanied by yet another girl in white who was crowned with

flowers -- ascending into the heavens. A Gascon priest travelling from

the opposite direction had the same vision. The next day, they related

what they saw

to villagers in town, and they all seemed to intuit the meaning of the

vision, so they gathered at the Cousin house only to find that Germaine

had died there on her bed of vines and twigs underneath the staircase

in her stable, among her sheep. She was discovered by her father that

morning when she failed to show up to tend the

flocks. When he found her, her yarn rosary was in her hands.

She was buried, unembalmed, in front of the pulpit of the same church

at which she attended Mass each day, and was apparently forgotten for a

time.

Then, a little over forty years later, in 1644, her grave was opened so

that the body of one of her relatives could be buried there. When her

body was uncovered, it was found to be as fresh as the day it was laid

to rest. Her body was displayed to the public, prayers went up, and

miracles began to happen in great abundance, the first of these being

the cure of a woman's infant son who was expected to die. In gratitude,

the woman purchased a lead coffin to hold St. Germaine's body. This

casket was moved to the sacristy, and when opened again in 1661, her

body was still found to be intact. Wanting to be more sure about this

sign of possible sanctity, the priest had the area around the pulpit

dug up to determine the state of other bodies buried there, and found

that only St. Germaine's was intact.

In 1700, her lead casket was opened again with the same results. The

cause for her beatification was begun, but was stalled for a time --

and then came the

demonic French Revolution, which left not even St. Germaine untouched.

In 1793, revolutionaries threw her body into a pit and poured quicklime

over it, destroying some of it. But what remained was salvaged, praise

God. It's said that the revolutionaries were three in number, and that,

after committing their evil, all three were almost immediately struck

by bodily infirmities, with one never repenting, and the other two not

only repenting, but being cured through St. Germaine's interecession.

Things settled down in France, and the cause for her beatification was

resumed in 1850. The Catholic Encyclopedia tells us that the

documents

attested more than 400 miracles or extraordinary graces, and thirty

postulatory letters from archbishops and bishops in France besought the

beatification from the Holy See. The miracles attested were cures of

every kind (of blindness, congenital and resulting from disease, of hip

and spinal disease), besides the multiplication of food for the

distressed community of the Good Shepherd at Bourges in 1845.

She was finally canonized on June 29, 1867. Her reliquary -- now no

longer made of lead, but of a more precious and beautiful metal --

remains in the little church in which she was interred, but some of her

relics were later moved to a lovely Romano-Byzantine basilica that was

built

in Pibrac in her honor -- la Basilique Sainte-Germaine.

St.

Germaine's reliquary St.

Germaine's reliquary

La

Basilique Sainte-Germaine in Pibrac

Pibrac has

become a great place of pilgrimage, and

every year on June 15, her feast day, her relics are processed from

l'Eglise Sainte-Marie Madeleine to the la Basilique Sainte-Germaine.

Then a pilgrimage is made to the house in which St. Germaine's family

lived, and the little stable in which she devoted herself to God and

attained holiness. Along the way, the Way of

the Cross is made.

St. Germaine -- "la bergère au pays

des loups" ("the shepherdess in the country of wolves") as the

playwright Henri Ghéon called her -- is the patroness of the weak,

abused, sick, disabled, poor, and shepherds. She's portrayed in art as

a young woman with her

sheep, a shepherd's crook, a distaff, and/or flowers.

Customs

A prayer for the day is a translation of a French one:

Remember, O

sweet Germaine, your brothers and sisters who groan and who

suffer in this vale of tears. Remember those who hope in you, who await

your help with their trials, your consolation in their sorrows.

Remember that you, too, groaned, that you, too, cried, that you,

too, knew poverty, isolation, humiliation, and suffering. And now, in

your glory, remember our miseries; in your power remember our

infirmities; in your happiness, remember our tears. Teach us, in your

school of sweetness, of your patience, your faith, and your love. Then,

at our deaths, receive us into our eternal home.

Or there is the Litany to St.

Germaine Cousin de Pibrac, written by the uncanonized,

controversial

Bretonne mystic Marie-Julie Jahenny (1850-1941).

There is no special music or food associated with her feast that I know

of; St. Germaine is not as well known as she should be outside of

France, alas, so we in other parts of the world can come up with our

own practices that may become traditions in the future. Perhaps you can

read to your children the story of Cinderella, then tell them the story

of St. Germaine, asking them to find the similarities. The story as

told by Perreault: Cinderella

(pdf)

But most important today is learning the lessons of St. Germaine's sad

but awe-inspiring life, and pondering the bliss she is enjoying now in

Heaven. Consider how spoiled most of us are, how devoted to pleasures

and to self. We parade ourselves on the internet, constantly looking

for attention. We wallow in resentments and pettiness, and act on our

sinful envies. And then there is St. Germaine, whose sufferings most of

us can't begin to imagine, but who lived a life of such grace and

beauty that almost all the world is put to shame in comparison. Asking

God to make us more like her is absolutely the best use of the day.

Footnotes:

1 She is mostly known as "Sainte Germaine

de Pibrac" in France. Her name, in any case, is pronounced "Zher-men

Coo-zaih" -- where the N in "Cousin" is not pronounced, and the final

vowel sound is kind of similar to the vowel sound one makes when saying

"wah" as in a mocking crying sound.

2 Scrofula is now usually called

lymphadenopathy, and is caused by bacterial infection, including

infection by the

bacterium that causes

tuberculosis. In medieval times, it was thought to be cured by the

touch of the reigning monarch. This practice in England goes back to

since at least Henry I, and in France to at least King St. Louis IX.

In England, the monarch would touch the neck or face of the afflicted

and hang a coin around his neck while offering prayer to God, to the

Blessed Virgin and other Saints, and citing Sacred Scripture (Mark

16:14-20 and John 1:1-14).

|