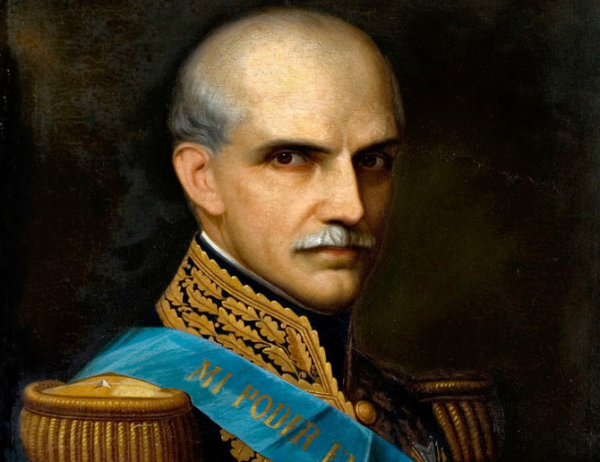

Gabriel Garcia Moreno, Statesman and

Martyr

by Gary Potter

|

On the Feast of the Transfiguration, August 6, 1875, a

statesman, whom many would call the greatest the world has known since

the so-called Reformation, was cut down by Masonic assassins on the

porch of the cathedral in his nation’s capital. Moments before, until

lured outside by a false message that he was urgently needed elsewhere,

he had been adoring the Blessed Sacrament.

Fallen from the porch and lying stretched out on the ground, his head

bleeding, his left arm severed and right hand cut off by blows of a

machete, the illustrious victim recognized his assailants — recognized

in the sense of understanding for whom they acted. Some accounts say he

gasped his last words, others that he was able to cry them out

defiantly. All agree on the words themselves: "Dios no muere!" "God

does not die!"

Striking as they were as a summing up of the moment — they amounted to

saying, "You may murder me, but you can never kill the One whom men

like you really want dead" — other words voiced by the felled leader on

other occasions can be compared to them for aptness. These would

include, above all, the words of his political creed, one for whose

realization he spent himself in life and would finally die, words that

were and are a summing up of the whole of Christian doctrine when

applied to the sphere of politics, the means by which the life of a

society is governed: "Liberty for everyone and everything, except for

evil and evil-doers."

Insofar as the man was guided by that creed in his governance of the

nation, we can understand how it was that what he wrought would become,

as Pope Leo XIII described it: "The model of a Christian state."

The nation was Ecuador. The man was Gabriel Garcia Moreno, twice

President of the Republic and throughout most of his adult life the

nation’s most commanding figure as a lawyer, legislator, scholar and

soldier, as well as statesman. This essay is about him — rather more

about him as a man than in terms of his career.

That is not to say his achievements will be ignored, but it is not

necessary to detail events and developments in Ecuadorian history to

appreciate them. Still, it is desirable to have some idea of the

history of Ecuador and of the region, especially before Garcia Moreno

arrived on the scene. It is, if only because many in the U.S. are

inclined to suppose that everything south of the Rio Grande,

geographically and politically, if not culturally, is an extension of

their own part of the Hemisphere, or ought to be. When they see it is

not, or does not wish to be, they chalk it down to the cultural

difference, and that difference is defined for them by Latin America

being Catholic.

To most in the U.S., that difference has always made Latin America

"backward" or "less developed." It is taken as one of the indices of

this supposed backwardness that governments in Latin America have often

been headed by authoritarian leaders — usually called "strongmen" or

"dictators" by U.S. news media.

If the views on Latin America held by many U.S. Catholics, perhaps

including some readers of these lines, are colored by the majority’s

notions, it should not be surprising. Most men are susceptible to the

influence of a majority. Further, the views are not entirely mistaken.

The cultural difference between Latin America and North America is very

great, or at least it was before McDonald’s and MTV, and the

difference, indeed, has its roots in religion. Where U.S. Catholics can

let themselves be led astray by majority notions is in accepting the

view that Catholic culture and its fruits are necessarily "backward" —

i.e., inferior.

That includes the political fruits. Gabriel Garcia Moreno was certainly

the kind of authoritarian ruler who would be — who is — condemned as a

"strongman," as if being one of those were necessarily evil. Is it?

Sometimes even the leading organs of secular liberalism seem unable

quite to make up their mind on this question.

Illustrative of this curious ambiguity is the Encyclopedia Britannica’s

online article about Gabriel Garcia Moreno. Therein it is actually

admitted, if but grudgingly, that his rule was, well, "often effective

in its reformist aims." Still, it "eventually cost him his life" since

it was "oppressive." That, of course, was due to his being the

"initiator of a church-oriented dictatorship." Further, "versed in

political theory…he became convinced that the remedy for his nation’s

political and economic plight was the application of moral principles

by a powerful leader." (Moral principles? Good Lord! Would they be more

excusable if applied by a weak leader or one not versed in political

theory?) If it was due to them that Garcia Moreno somehow "reduced

corruption, maintained relative peace, and strengthened the economy,"

he also "placed education under the Roman Catholic Church, signed a

concordat with the Vatican, and officially dedicated Ecuador to the

Sacred Heart." No wonder, then, that "he was assassinated by a group of

young liberals." (And no wonder, either, that the Encyclopedia

Britannica cannot limit itself simply to reporting his positive

achievements.) As for the "young liberals" who murdered him, we have

already seen who they really were. (Signed checks in the pockets of one

provided hard evidence.)

For most Americans, Ecuador is probably among the lesser-known Latin

American nations. To speak of nations, of course, is to speak of

peoples. Some islands belonging to Ecuador are very well known. These

are the Galapagos, 600 miles west of the mainland in the Pacific Ocean.

TV documentaries have made them, if not Ecuadorians, famous as the home

of giant sea turtles, iguanas, and other exotic forms of animal life.

About the size of Colorado, mainland Ecuador is not one of South

America’s larger countries. With no more than six percent of its land

being arable, it is not an agricultural power in the world. It is an

oil-producing nation, however, and also exports other raw materials and

some finished goods. Its population of 12 million is 95 percent

Catholic.

Topographically, two ranges of the Andes Mountains run north and south,

dividing the country into three zones: hot and humid lowlands along the

Pacific Ocean coast; temperate highlands between the two ranges; and

tropical jungle in the east (where the oil is located). The capital,

Quito, is in the highlands. Historically, there has been political

rivalry, sometimes exploding into an outright fight, between

conservative forces centered in Quito and liberal elements with their

base in the chief port and second city, Guayaquil.

Gabriel Garcia Moreno, born on Christmas Eve, 1821, was a native of

Guayaquil. Once his youth was behind him, however, no one would ever

accuse him of liberalism.

History knew no independent nation of Ecuador until nine years after

his birth. Prior to that, history of the land of which we can be sure

began in the 15th century with the subjugation of native inhabitants by

Incas from the south. Inca rule lasted little more than 50 years. It

ended when Spaniards under Sebastian de Belalcazar, a lieutenant of

Francisco Pizarro, the great conquistador, decisively beat the last

Inca warriors defending the northern part of their empire. That was in

1534. There followed nearly three centuries of Spanish government.

Nowhere in Latin America did the Spanish ever try simply to exterminate

native peoples as did the Anglos in North America. Evangelization was

always integral to their colonial enterprise in the Western Hemisphere.

If that made them baptizers instead of killers, they also had to be

civilizers. (They knew that men are not saved simply by baptizing them.

They must also lead morally upright lives.)

Though the civilizing mission of the Spanish deserves more honor and

praise than it receives today, or will receive as long as political

correctness keeps "multiculturalism" a dominating idea on the

intellectual landscape, Catholics should never falsify history. We

ought to acknowledge that the Spanish record in the Americas, glorious

as it was, was not without stain. For instance, development of the

territory that would become Ecuador was frustrated during the early

Spanish years by a series of local civil wars fought among captains

motivated by nothing but greed and ambition. After that, rapacious

individuals, ignoring the expressed will of Spain’s monarchs and

remonstrances of the Church, would abuse and exploit native Indians to

the point of enslaving many. This scandal was made worse with the

importation of slaves from Africa, most of whom arrived in the region

via the Colombian port of Cartagena.

Our reference to that port city and center of the slave trade is not

accidental. To the extent that such a place can be sanctified by the

actions of one man, it was the case of Cartagena from 1610 to 1654 when

it was the arena of St. Peter Claver’s apostolic efforts.

To the south, in the capital of the Viceroyalty of which Ecuador was

then a part, that of Peru, the life of another holy person during some

of those same years tempered what inhumanity and injustice existed at

the time. This was St. Rose of Lima.

A contemporary and friend of hers in Lima, the Dominican lay-brother

St. Martin de Porres, represented in his own person, as the son of a

Spanish nobleman and woman of color, a melding of races that was then

taking place and which has always been characteristic of Catholic,

Hispanic culture. (Nothing like it on as wide a scale ever took place

in Protestant North America. Fifty-five percent of our population,

after all, is not mestizo, as is that of Ecuador today.)

If sanctity could and did exist alongside an evil like slavery in

17th-century Spanish America, it was owed largely to the labors of

religious orders. Those labors included, as we have said, the unceasing

effort to civilize, especially through education, as well as baptize.

Tragically, much of the orders’ work was undone in Ecuador and

elsewhere in Latin America in the last decades of the 18th century. The

poison of the Enlightenment had spread into and infected Spain by then,

and with the infection came the fever of the Revolution. As a result,

the Jesuits were expelled from Ecuador in 1767, as were other orders

soon afterward. The consequences were awful. For example, it is

estimated that 100,000 Indians living in the neighborhood of 33

Dominican missions in the jungle part of the country reverted to

paganism after the sons of St. Dominic were expelled.

If the effort to promote and extend the sway of the Faith made possible

the continuance of Spanish rule despite its deficiencies, the rule

could not endure when the effort ceased. That is to say, the Spaniards

who abandoned the Faith for the Revolution soon paid for their sin. At

home, their country was militarily occupied by Napoleon. In the

Americas, their lands were torn from them one by one.

The movement toward independence from Spain began early in the 19th

century. It is much misunderstood in North America. In numerous places

it was far from revolutionary, though that is how it is always

portrayed. Mexico is a case in point. The Spanish government at the

beginning of the 19th century was liberal and corrupt beyond

description. When its administration in Mexico was finally overthrown,

the first leader of the independent nation was not a Masonic President

like Benito Juarez later on, but a Catholic Emperor, Agustin de

Iturbide. (He took the name Agustin I. That he was a faithful son of

the Church is underlined by the fact that he did not simply crown

himself like Bonaparte. He was anointed monarch by the Archbishop of

Guadalajara.)

In South America, the leading independence figure, by far, was Simon

Bolivar, born in 1783 in Caracas in what is now Venezuela but was then

part of the overseas Spanish territory of New Granada. His name is well

known in the U.S. We even have towns named after him, like Bolivar,

Missouri. Beyond that, we hear he was a Freemason and assume a great

deal from the fact, not all of which is wrong — far from it. If we hear

he was exposed to the writings of such as Locke, Hobbes, Voltaire and

Rousseau while being educated in Europe, we may rightly assume still

more. However, in La Carta de Jamaica (A Letter from Jamaica), a

political declaration written in exile in 1814, he proposed for South

America a form of government consisting of a bicameral legislature with

an elected lower house such as might be expected, but also with a

hereditary upper house and with a president who would serve for life.

Thus we see that from the very beginning, and in the mind of the

veritable father of South American independence, government was

envisioned that featured at its head a leader whose term in office was

not subject to the control of any electorate — a virtual caudillo, to

use the Spanish word English-speakers approximate when they talk about

a "strongman".

Before retiring from politics in 1830 — he would die before the end of

the year, heartsick over the disunity and factionalism he saw rising

all around him — Bolivar served as President of both Gran Colombia

(consisting of today’s Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador) from 1821 to

1830 and Peru from 1823 to 1829. His occupancy of this dual presidency

underscores something important. Bolivar did not seek to bring into

existence the individual nation-states of South America with which we

are now familiar. He thought in terms of continents. The fulfillment of

his vision could have led to a United States of (South) America.

Whether it would have endured or eventually come apart, as the U.S.

nearly did in the 1860s, the possibility of it suggests one of those

interesting "what if" questions beloved by history buffs: What if there

had been in this Hemisphere and in the world during the past two

centuries a united South America counter-weighing the U.S. in the

north?

A unifying principle would have been needed for it to happen. The U.S.

found one in a conception of freedom compatible with its regnant

Protestantism. Latin American unity would have had to form around some

principle derived from the One True Faith, or even the Faith itself.

From very early on, the U.S. has been alive to the possibility of

exactly that happening, or of even one of the American Hispanic nations

emerging as a real power on the world stage, a Catholic one.

Accordingly, Catholic political leaders, which is to speak of leaders

sympathetic to Catholic social order, have found themselves undermined

and seen the careers of men friendly to the spread of alien ideas

promoted — ideas like the notion of freedom imagined as the license to

do as one pleases instead of the Catholic understanding of it as the

freedom to choose between salvation and eternity in Hell. Iturbide saw

it. The very first envoy sent from the U.S. to Mexico after that nation

became independent presided over his dethronement. Once he was

eliminated, "Freemasonry, so actively promoted in Mexico by the first

minister from the United States, Joel R. Poinssett" — we are quoting

from the old Catholic Encyclopedia (1913) — "began gradually to lessen

the loyalty which both the rulers and the governed had manifested

toward the Church."

The anti-Catholicism of U.S. policy in Latin America has sometimes been

stated explicitly by our leaders. It was by Theodore Roosevelt when he

paid a visit to South America at the turn of the 20th century. "While

these countries remain Catholic," he said, "we will not be able to

dominate them."

To be sure, the policy has not often been reflected in speech quite

that bald, but it has been blatant in a number of historical actions,

as when the U.S., in violation of its own Monroe Doctrine, assisted

England in its invasion of the Western Hemisphere and war against

Argentina in the Malvinas (called the Falklands by England) in 1982.

Gabriel Garcia Moreno would have been the ideal leader of a great

united, Catholic South America. Had he been born a few decades earlier,

he might even have been the man to forge it, as Simon Bolivar finally

proved not to be. The small nation of Ecuador, however, would be the

only theater he knew for the exercise of his very large political

talents. He reached its stage none too soon.

For eight years (1822-30) the nation, as we have already heard, had

been part of the confederation of Gran Colombia, the other sections

being Colombia and Venezuela. Mainstream history books speak of various

territorial and economic disputes leading to the break-up of the

confederation, but we have just finished noting the existence of forces

in the world that would favor such a development, if they did not

foment it.

Whatever, the first fifteen years of Ecuadorian independence were

dominated by two men, Juan Jose Flores and Vicente Rocafuerte. The

former hailed from Quito and had his main support from the country’s

great landed families. Rocafuerte was more of an ideologue, his support

coming from the wealthy bourgeois merchants who controlled Guayaquil

and were influenced by 19th-century liberalism of the kind that had

anti-clericalism as an integral feature. Neither man was much concerned

for the welfare of ordinary Ecuadorians, including the native Indians,

but kept the country fairly stable as they alternated the presidency

between themselves.

In the mid-1840s a series of younger men came on the scene. None was

really fit to serve as president of the fledgling nation, all aspired

to do so, most proclaimed themselves liberal, and as many as did were

ready to commit the vilest acts to prove it. The chaos their rivalries

produced brought Ecuador very near to disintegration before Garcia

Moreno finally took power for the first time in 1859.

We have said it is not necessary to detail here events and developments

in Ecuadorian history in order to appreciate the achievements and

personal qualities of Garcia Moreno. Accordingly, we are not going to

spend time exploring the intramural squabblings of the liberals or

tracing the steps taken by Garcia Moreno to overcome them, except to

say two things.

The first is that he sometimes had to fight during his rise to power —

not figuratively fight, but fight in battle with gun or sword in hand

against one or another of the liberals. Though he was not formally

trained as a military man, a willingness to risk his life and apparent

inborn sense of what was strategically wise as well as tactically sound

won him the victories that were necessary. So it is that we can count

soldiering among his accomplishments.

The second thing to say is that when he was a young man first making a

name in politics, it was as a liberal. When we go further and say that

was very much to the chagrin of his mother and also his first mentor,

it becomes necessary to speak briefly about his early life, and that

raises the subject of sources.

Students who wish to know more about Garcia Moreno than can be told in

this article but who do not read Spanish will have few directions in

which to turn. Further, what little exists in English will often differ

from what is read here. For instance, most of the English-language

sources have Garcia Moreno assassinated on the steps of the National

Palace in Quito, whereas our readers have already heard that it was on

the porch of the close-by cathedral. That is because we are drawing

mainly from a biography that was written by the French Redemptorist

priest, Rev. P.A. Berthe, soon after the death of Garcia Moreno. The

biography, Garcia Moreno, President of Ecuador, was translated by Lady

Herbert and published by Burns and Oates in London in 1889, and never

since, making this English version a book that can now be found only in

a few libraries. The late Hamish Fraser did bring out an abridgment of

Lady Herbert’s translation, but it is no longer available. However,

Fraser’s sponsorship of the book is one of two reasons for our relying

on Fr. Berthe instead of other sources.

During the past half-century, the Church’s authentic social doctrine

has had no champion in the English-speaking world more valiant than

Hamish Fraser. A former Communist Party labor organizer on the docks of

London, who converted to the Faith and for a long time edited the

invaluable and much-missed publication Approaches, Fraser was a student

of the life and career of Garcia Moreno. Not simply did he hail him in

print as "the greatest statesman we have had since the Reformation,"

his admiration was such that he named his home in Scotland for him,

Casa Garcia Moreno. If Fr. Berthe’s biography was good enough for

Hamish Fraser, it’s good enough for us.

The second reason for relying on it: It is Catholic; the happenings of

which it speaks are viewed with the eyes of faith. This means it

reports things that are ignored in other writings, especially things

that relate to Garcia Moreno as a man and which attest to the

thoroughness of his Catholicity. An example: Fr. Berthe quotes the rule

for his daily life that Garcia Moreno wrote down in his own hand on the

back page of the copy of The Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis

that was found in his pocket after his assassination. There could be no

more eloquent testimony to the man’s determination to stay close to

God. (We shall soon read it for ourselves.)

As for his early life, his father, Don Gabriel Garcia Gomez, was born

in Spain and became a successful merchant after emigrating to Ecuador.

It was there that he married Dona Mercedes Moreno. The couple had eight

children — five sons and three daughters — of whom Gabriel was the

youngest. He was still a boy when his father died suddenly. Not merely

was the family then bereft of its head, Don Gabriel had recently lost

nearly all his money in a business reversal. This left the family,

formerly quite well off, in real poverty. In fact, it was impossible

for young Gabriel to continue with the schooling he had just begun.

Fortunately for him and the future of Ecuador, Dona Mercedes was as

persuasive as she was pious. She was able to prevail on a local

Mercedarian priest of some learning, Fr. Jose Betancourt, to take on

her son as a private pupil. The boy justified the cleric’s attention by

mastering Latin in ten months! Before he was 15 he had learned

everything the priest had to teach him.

Earlier, his mother’s appeal to Fr. Betancourt had assured his basic

schooling. Now it was his mentor, Fr. Betancourt, who persuaded the

authorities at the University of Quito to admit young Gabriel,

penurious as he was, as a student. An older, married sister living in

Quito, Josepha, was able to provide him a place to stay. So it was

that, still a boy, he left home for the capital in September, 1836.

There he would become a young man.

He discovered science at the university. The life of his country, as

well as his own, would have been profoundly different had he given in

to his passion for the subject and made a career as a botanist or

chemist. However, it would be with a degree in law that he eventually

left the university. Armed with his degree, he opened a legal practice

and began to become politically active — as a liberal.

If he did not give in to his passion for science, he did surrender to

others. In this regard, we shall continue to follow Fr. Berthe’s lead.

That is, if we are ignoring here the details of Ecuadorian history and

Garcia Moreno’s rise to power, there is less reason for us to dwell on

the period during his young manhood when he drifted away from faithful

religious practice and for a time was guilty, like young St. Augustine,

young St. Ignatius of Loyola and other canonized saints who could be

named, of personal moral failures. Fr. Berthe is quiet about this. So

shall we be.

Though it will not do to dwell on the period, it needs to be noted that

it corresponded to that of his political liberalism, and it must be

observed that his return to religion paralleled the change in his

political views, and this development would prove decisive in his

taking the course he did as leader of the nation.

One historian (Frederick B. Pike) has put the matter like this: "His

personal experiences seem to have influenced his attitude toward

governing his country. In his own case, liberalism and religious

indifference had gone hand-in-hand with personal debauchery and lack of

self-control, while religious fervor had been intertwined with a life

of rigorous self-control and Spartan discipline. After coming to the

presidency, Garcia Moreno set out to rekindle religious fervor among

Ecuadorians in the expectation that the entire country could be made to

undergo a transformation paralleling his own."

Before we consider what he did with political power once he attained

it, there has to be mention of two factors that mightily helped Garcia

Moreno fortify within himself the personal and political transformation

begun by religious conversion. One was his marriage to Dona Rosa

Ascasubi, the member of an aristocratic Quito family who brought to

their union a strong character as well as large fortune. The other

factor was a period of exile that he spent in Paris. It was there that

he actually returned to the practice of the Faith. Louis Veuillot, the

very great 19th-century French Catholic journalist, would write of that

in a tribute he penned for his newspaper, l’Univers, in September,

1875:

"Paris, Christian on the one hand and savage on the other, gives the

world the spectacle of a fight between two opposing elements. It has

schools for priests and martyrs, and others for anti-christs, idols,

and executioners. The future President and Missioner of Ecuador had

before his eyes good and evil. When he returned to his distant home,

his choice was made. He knew where to find true glory, true strength,

and how to become the true workman of God."

Inasmuch as it was in 1848 that Garcia Moreno lived in Europe, he also

had before his eyes all of the violence and disorder of that year’s

revolutionary upheavals in France, Germany, Austria, Italy and

elsewhere. He could see where his own country was likely headed —

unless a "true workman of God" or (in the words of the Encyclopedia

Britannica) a "powerful leader" applied the kind of "moral principles"

(still quoting the Britannica) that could prevent it.

More specifically, what Garcia Moreno saw when he looked at his own

country was one divided by regional resentments (the coast vs. the

highlands), divided by class (the bourgeoisie of Guayaquil vs. the

landed families of the interior), divided between whites and Indians

and even blacks from the old slavery days (they are still 10 percent of

the population). There was not even a single language to unite the

country, many of the Indians being non-Spanish-speaking. The one thing

all Ecuadorians — or nearly all — had in common was Catholicism. Even

liberals who did not practice it had it in their background. Their

culture was Catholic. A "true workman of God" could build on that.

Garcia Moreno did. He had a blueprint: L’Histoire Universelle de

l’Eglise Catholique, an immense work of 29 volumes written by Rev. Rene

Francois Rohrbacher that Garcia Moreno read no fewer than three times.

Fr. Berthe describes L’Histoire: "It sets forth in the most exhaustive

form the whole history of the Church, politically and socially, proving

her to be the head of the great social body, of which the State is the

arms, and which both kings and people must obey. Hence there should be

neither struggle nor divorce between Church and State, but the most

perfect harmony, from the subordination of the State to the Church."

No reader should let himself be swept into clericalism by those words.

Nothing but harmony should exist between Church and state, but the

Church consists of more than clerics. She is also the body of her

beliefs and teachings, and it has sometimes happened in history that

rulers have had to uphold that body when clergy and episcopacy did not.

King St. Louis IX of France, for instance, had to enforce corrective

measures against corrupt and abusive bishops and priests (see From the

Housetops No.45). In regard to Ecuador, it will be remembered that

religious orders had been expelled from the country. That meant there

were not many priests and religious left to minister to the faithful

except local ones. By the time Garcia Moreno came to power, too many of

them had become — not to mince words — degenerate and even dissolute.

Not surprisingly, they criticized the President for being "fanatical"

in his Catholicism. His solution was to lift the ban on foreigners so

the locals could be replaced by them. Further, he basically turned over

the running of the nation’s schools, from the primary ones to the

polytechnical training college in Quito, to the religious orders,

especially the Jesuits. Liberals still have not forgiven him for that,

but the fact is that probably no nation in Latin America at that time

made greater strides in education than Ecuador.

His educational policy was not the only reason Garcia Moreno was

labeled a "fanatic". Under his presidency, not simply was the Faith

established as the religion of the state, the existence of no other

being officially recognized. Citizenship, by law, depended on being a

member of the Church. Enacting such a law was nearly as extraordinary

in the 19th century as it would be inconceivable in the 21st, but the

Catholic scholar Christopher Dawson reminds us in his book

Understanding Europe that "for more than a thousand years the religious

sacrament of baptism which initiated a man into the Christian community

was also a condition of citizenship in the political community." That,

of course, was before society became "Judaeo-Christian" or, as the U.S.

seems on the verge of becoming, Islamo-Judaeo-Christian.

The reader already knows from early in this article that under Garcia

Moreno Ecuador, by an act of its congress, was dedicated as a nation to

the Sacred Heart of Jesus. What will come as a shock to anyone

sufficiently ignorant of history as to imagine that the century or so

before Vatican II was some kind of golden age for the Church is this

fact: When the Papal States were overrun by the troops of Victor

Emmanuel in 1870 and the pope became a virtual prisoner in the Vatican,

the government of Garcia Moreno was the only one in the entire world to

protest. That was not all. Victor Emmanuel’s conquest of the Papal

States having deprived the Holy See of the main source of its revenues,

Garcia Moreno had the Ecuadorian Congress vote a tithe of ten percent

of national monies for the financial support of Bl. Pope Pius IX.

Space does not allow for enumerating all of the material works

undertaken by the Martyr-President for the improvement of the lives of

Ecuadorians of every class and ethnic group. Besides the schools he

built, there were hospitals and roads. A railroad over the mountains

between Quito and Guayaquil was begun so that the two main sections of

the country, the Costa and the Sierra, would be brought together.

Garcia Moreno also saw to the planting of countless eucalyptus trees

from Australia to stop the soil erosion that began when poor Indians

cut down ground cover for fuel.

No enumeration of such works and many others accomplished by Garcia

Moreno as President of Ecuador can provide for a complete appreciation

of his importance to the nation. Perhaps we can get nearer to that by

citing some of what his liberal opponents had to do in order to

dismantle his achievements once they eliminated him. To cite but a few

of their measures (they did complete the railroad), after proclaiming

freedom of religion, they legalized civil marriage and divorce and

lifted controls on the (liberal) press. It should go without saying

that they abolished the tithe to the Church, removed religious orders

from state schools, tore up the Concordat with Rome, and revoked the

republic’s dedication to the Sacred Heart. Eventually they expelled

(once again) religious orders from the country. In other words, they

remade Ecuador from a "model Christian state" into a typical modern one.

But what was Garcia Moreno like? Physically, he was tall, powerfully

built and, judging from his portraits and word descriptions of him,

strikingly handsome with a high and broad forehead. By the time of his

murder his hair was white.

It was a good thing he was strong. Otherwise he could never have pushed

his body the way he did in the service of his countrymen. Urged by

friends and family to slow down, he would say, "When God wants me to

rest, He will send me illness or death."

Such heedlessness of self would be foreign to a man who is "prideful,"

"ambitious," "hungry for power," "arrogant" — all words (among the more

polite) used by Garcia Moreno’s liberal enemies to describe him.

One word they never used: greedy. Charges of corruption would have to

be backed by evidence, and they knew they could never come up with

that. If only by indirection, Fr. Berthe explains why: "Garcia Moreno

believed that the head of a State is simply an instrument in the hands

of God for the good of the people. He was intimately convinced that the

Catholic law was as binding on nations as on individuals, and that the

first duty of the head of the State in this nineteenth century was to

re-establish the Church in all the rights of which the Revolution had

deprived her… ‘Let us do everything for the people through the Church,’

he would say; ‘he who seeks first the Kingdom of God will have all

things added to him.’"

Elsewhere, Fr. Berthe writes of Garcia Moreno that "his passionate love

for justice was united to an exquisite tenderness and kindness of heart

towards all who suffered. The poor knew it well, and one saw him

continually, on his way home from his office, surrounded by people of

every class, to whom he would listen patiently, giving advice to one,

money to another, and sending all away grateful and contented. If all

his deeds of charity were known, or we had space to record them, they

would alone fill a volume."

Probably we should emphasize Fr. Berthe’s words that Garcia Moreno’s

love of justice was passionate. We can see that in his reply to a man

seeking clemency for a group of anarchists sentenced by the courts to

die. "We have enough assassins in this country without them," he said.

"Your sympathy is roused by the fate of the criminals; mine is reserved

for their victims."

His reference to assassins reminds us of his own end. According to Fr.

Berthe: "Not only did he not fear death, but like the martyrs he

desired it for the love of God. How often did he write and utter these

words: ‘What a happiness and glory for me if I should be called upon to

shed my blood for Jesus Christ and His Church.’"

Did he mean that? Had he been truly transformed, truly converted, when

he abandoned the ways of his young manhood and returned to religion? We

have heard here about some of the laws he saw enacted in favor of the

Church, in favor of the Faith. Let us add to the picture that he

attended Mass every day, that he recited the Rosary every day, that he

spent a half-hour every day in meditation. Was he sincere in all this,

or was all of it a pose, a kind of public-relations campaign in days

before PR existed? If he was seen at Mass every morning, was that

simply an 1870’s version of the photo-op? In short, was Garcia Moreno

what he seemed, or a hypocrite? The question inevitably arises in a day

like ours when belief in the moral rectitude of any political leader

would seem misguided if not positively na´ve or plain stupid.

It is easy to suppose that, dedicated as he was to defending the

Christian social order, Garcia Moreno would readily have recognized the

social utility of hypocrisy, though nowhere do we find him speaking of

it. (By "social utility," all we mean is that it is more useful to a

society — it is better off for it — if its members, especially its

leading ones, do not parade their vices shamelessly, as is commonplace

today. Of course it is far better for the individual — and society — if

he has no vices to parade.)

If there is no record of Garcia Moreno speaking of the value of

hypocrisy as a social lubricant, Fr. Berthe does quote him talking

about hypocrisy as such. This was when he was accused of it on account

of letting himself be seen practicing the Faith publicly. "Hypocrisy,"

he said, "consists in acting differently from what one believes. Real

hypocrites, therefore, are men who have the Faith, but who, from

respect, do not dare to show it in their practice."

If that were not all the answer needed as to whether Garcia Moreno was

a hypocrite, it can be demonstrated in various ways that the private

man and public one corresponded perfectly. No demonstration could be

clearer, however, than citing the rule for himself that he wrote down

in his copy of the Imitation of Christ. It was mentioned earlier.

Bearing in mind that he did not know death awaited him outside the

cathedral on August 6, 1875, that he did not know the Imitation would

be found in his pocket that day, and that therefore the rule would ever

be read by anyone else, here it is in its entirety:

"Every morning when saying my prayers I will ask specially for the

virtue of humility.

"Every day I will hear Mass, say the Rosary, and read, besides a

chapter of the Imitation, this rule and the annexed instructions.

"I will take care to keep myself as much as possible in the presence of

God, especially in conversation, so as not to speak useless words. I

will constantly offer my heart to God, and principally before beginning

any action.

"I will say to myself continually: I am worse than a demon and deserve

that Hell should be my dwelling-place. When I am tempted, I will add:

What shall I think of this in the hour of my last agony?

"In my room, never to pray sitting when I can do so on my knees or

standing. Practice daily little acts of humility, like kissing the

ground, for example. Desire all kinds of humiliations, while taking

care at the same time not to deserve them. To rejoice when my actions

or my person are abused and censured.

"Never to speak of myself, unless it be to own my defects or faults.

"To make every effort, by the thought of Jesus and Mary, to restrain my

impatience and contradict my natural inclinations. To be patient and

amiable even with people who bore me; never to speak evil of my enemies.

"Every morning, before beginning my work, I will write down what I have

to do, being very careful to distribute my time well, to give myself

only to useful and necessary business and to continue it with zeal and

perseverance. I will scrupulously observe the laws of justice and

truth, and have no intention in all my actions save the greater glory

of God.

"I will make a particular examination twice a day on my exercise of

different virtues, and a general examination every evening. I will go

to confession every week.

"I will avoid all familiarities, even the most innocent, as prudence

requires. I will never pass more than an hour in any amusement, and in

general, never before eight o’clock in the evening."

The medical examination of Garcia Moreno after he was killed showed he

was shot six times and struck by a machete fourteen. One of the machete

blows sliced into his brain.

Incredibly, he did not die immediately. When cathedral priests reached

him, he was still breathing. He was carried back inside and laid at the

foot of a statue of Our Lady of Seven Sorrows. A doctor was called, but

could do nothing. One of the priests urged him to forgive his killers.

He could not speak, but his eyes answered that he had already done so.

Extreme Unction was administered. Fifteen minutes later he was dead,

there in the cathedral.

One hundred and ten years afterward, in 1985, Pope John Paul II went to

the cathedral upon arrival in Quito, during one of his famous

"pastoral" foreign trips, this one to South America. It was part of a

pattern that was already familiar — going by motorcade from the airport

to the local cathedral for a quick prayer of thanksgiving for a safe

arrival and then a homily setting out some theme for the visit.

Naturally enough, the homily would refer to the local scene, including

local historical happenings. This writer knows that has been the

pattern because, as a journalist, I have covered the arrival of John

Paul II in numerous cities in the U.S. and elsewhere.

When I saw in a newspaper an abridged text of the pope’s remarks at the

cathedral in Quito in 1985, I could not believe what was omitted: any

reference to Garcia Moreno and his death at that spot. On the

supposition that reference to the event was edited out for space, I

stopped by the Ecuadorian embassy in Washington (it is not far from

where I live) and explained to an attache that I was interested in

knowing what the pope might have said about Garcia Moreno when he was

in Quito. I saw the attache’s eyes narrow when I mentioned the name of

the great man, but he promised to check on the matter. A day or two

later an underling phoned to tell me that, no, the Holy Father had not

referred to Garcia Moreno, "But, you know, this is not surprising. That

president is very controversial in our history."

If Garcia Moreno is too "controversial" to be honored in our day, here

is what Bl. Pope Pius IX, speaking of himself in the third person, had

to say in a public address in Rome on September 20, 1875:

"In the midst of all this, the Republic of Ecuador was miraculously

distinguished by the spirit of justice and the unshakeable faith of its

President, who showed himself ever the submissive son of the Church,

full of devotion for the Holy See, and of zeal to maintain religion and

piety throughout his nation. And now the impious, in their blind fury,

look, as an insult upon their pretended modern civilization, upon the

existence of a Government, which, while consecrating itself to the

material well-being of the people, strives at the same time to assure

its moral and spiritual progress. Then, in the councils of darkness

organized by the sects, these villains decreed the murder of the

illustrious President. He fell under the steel of an assassin, as a

victim to his faith and Christian charity…. For Pius IX, also, the

death of Garcia Moreno is the death of a martyr."

|

|

Back to Marian Apparitions Deemed

"Worthy of Belief" Back to Marian Apparitions Deemed

"Worthy of Belief"

Back to Being Catholic Back to Being Catholic

Index Index

|