|

Septuagesima 1 (also known as

"Gesimatide") and Lent are both

times of penance, Septuagesima being a time of voluntary fasting in

preparation for the obligatory Great Fast of Lent. So connected are

Septuagesima and Lent that the former is sometimes called,

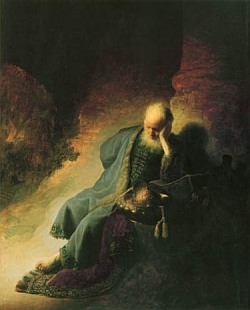

colloquially, "Pre-Lent." The theme of this season is the

Babylonian exile, the "mortal coil" we must endure as we await the

Heavenly Jerusalem. Sobriety and somberness reign liturgically; the

Alleluia and Gloria are banished

The Sundays of Septugesima are named for their distance away from

Easter:

- The first Sunday

of Septuagesima gives its name to the entire season as it is known as

"Septuagesima." "Septuagesima" means "seventy," and Septuagesima Sunday

comes roughly seventy days (actually 63 days) before Easter. This

seventy represents the

seventy years of the Babylonian Captivity. It is on this Sunday that

the alleluia is "put away," not to be said again until the Vigil of

Easter.

- The second

Sunday of Septuagesima is known as "Sexagesima, which means "sixty".

Sexagesima Sunday comes roughly sixty (actually 56 days) days before

Easter.

- The third Sunday

of Septuagesima is known as "Quinquagesima," which means "fifty" and

which comes roughly fifty days (actually 49 days) before Easter.

Quadragesima

means "forty," and this is the name of the first Sunday of Lent and the

Latin name for the entire season of Lent (the next season).

Each of those Sundays of Septuagesima focuses on a different Old

Testament patriarch:

| Septuagesima

Sunday |

Adam |

Sexagesima

Sunday

|

Noah |

Quinquagesima

Sunday

|

Abraham |

Throughout this short Season and that of Lent you will

notice a deepening sense of penance and somberness, culminating in

Passiontide (the last two weeks of Lent), that will suddenly and

joyously end at the Vigil of Easter on Holy Saturday when the alleluia

returns and Christ's Body is restored and glorified.

The station churches of the three

Sundays of Septuagesima:

Septuagesima: S.

Lorenzo fuori le mura

Sexagesima: S. Paolo fuori le mura

Quinquagesima: S. Pietro in Vaticano

Finally, you may be interested in reading "Meditations for

Lent" by St. Thomas Aquinas, which has a

reading for every day from

Septuagesima Sunday to the end of Lent. You can find it in this site's Catholic Library.

Reading

"The Mystery

of Septuagesima"

from Dom Gueranger's "The Liturgical Year"

The season upon

which we are now entering is expressive of several profound mysteries.

But these mysteries belong not only to the three weeks which are

prearatory to Lent: they continue throughout the whole period of time

which separates us from the great feast of Easter.

The number seven is the basis of all these mysteries. We have

already seen how the holy Church came to introduce the season of

Septuagesima into her calendar. Let us now meditate on the doctrine

hidden under the symbols of her liturgy. And first, let us listen to

St. Augustine, who thus gives is the clue to the whole of our season's

mysteries. 'There are two times,' says the holy Doctor: 'one which is now,

and is spent in the temptations and tribulations of this life; the

other which shall by then, and shall be spent in eternal

security and joy. In figure of these, we celebrate two periods: the

time before Easter, and the time after Easter. That which is before

Easter signifies the sorrow of this present life; that which is after

Easter, the blessedness of our future state... Hence it is that we

spend the first in fasting and prayer; and in the second we give up our

fasting, and give ourselves to praise.'

The Church, the intepreter of the sacred Scriptures, often speaks to us

of two places, which correspond with these two times of St. Augustine.

These two places are Babylon and Jerusalem. Babylon is the image of

this world of sin, in the midst whereof the Christian has to spend his

years of probation; Jerusalem is the heavenly country, where he is to

repose after all his trials. The people of Israel, whose whole history

is but one great type of the human race, was banished from Jerusalem

and kept in bondage in Babylon.

Now, this captivity, which kept the Israelites exiles from Sion, lasted

seventy years; and it is to express this mystery, as Alcuin, Amalarius,

Ivo of Chartres, and all the great liturgists tell us, that the Church

fixed the number of seventy for the days of expiation. It is true,

there are but sixty-three days between Septuagesima and Easter; but the

Church, according to the style so continually used in the sacred

Scriptures, uses the round number instead of the literal and precise

one.

The duration of the world itself, according to the ancient Christian

tradition, is divided into seven ages. The human race must pass through

the seven ages before the dawning of the day of eternal life. The first

age included the time from the creation of Adam to Noah; the second

begins with Noah and the renovation of the earth by the deluge, and

ends with this the vocation of Abraham; the third opens with

this first formation of God's chosen people, and continues as far

as Moses, through whom God gave the Law; the fourth consists of the

period between Moses and David, in whom the house of Juda received the

kingly power; the fifth is formed of the years which passed between

David's reign and the captivity of Babylon, inclusively; the sixth

dates from the return of the Jews to Jerusalem, and takes us on as far

as the birth of our Saviour. Then, finally, comes the seventh age; it

starts with the rising of this merciful Redeemer, the Sun of justice,

and is to continue till the dread coming of the Judge of the livng and

the dead. These are the seven great divisions of time; after which,

eternity.

In order to console us in the midst of the combats, which so thickly

beset our path, the Church, like a beacon shining amidst the darkness

of this our earthly abode, shows us another seven, which is to succeed

the one we are now preparing to pass through. After the Septuagesima of

mourning, we shall have the bright Easter with its seven weeks of

gladness, foreshadowing the happiness and bliss of heaven. After having

fasted with our Jesus, and suffered with Him, the day will come when we

shall rise together with Him, and our hearts shall follow Him to the

hightest heavesn; and then after a brief interval, we shall feel the

Holy Ghost descending upon us, with His seven Gifts. The celebration of

all these wondrous joys will take us seven weeks, as the great

liturgists observe in their interpretation of the rites of the Church.

The seven joyous weeks from Easter to Pentecost will not be too long

for the future glad mysteries, which, after all, will be but figures of

a still gladder future, the future of eternity.

Having heard these sweet whisperings of hope, let us now bravely face

the realities brought before us by our dear mother the Church. We are

sojourners upon this earth; we are exiles and captives in Babylon, that

city which plots our ruin. If we love our country, if we long to return

to it, we must be proof against the lying allurements of this strange

land, and refuse the cup she proffers us, and with which she maddens so

many of our fellow captives. She invites us to join in her feasts and

her songs; but we must unstring our harps, and hang them on the willows

that grow on her river's bank, till the signal be given for our return

to Jerusalem. She will ask us to sing to her the melodies of our dear

Sion: but how shall we, who are so far from home, have heart to 'sing

the song of the Lord in a strange land'? No, there must be no sign that

we are content to be in bondage, or we shall deserve to be slaves

forever.

These are the sentiments wherewith the Church would inspire us during

the penitential season which we are now beginning. She wishes us to

reflect on the dangers that beset us; dangers which arise from

ourselves and from creatures. During the rest of the year she loves to

hear us chant the song of heavne, the sweet Alleluia; but now, she bids

us close our lips to this word of joy, because we are in Babylon. We

are pilgrims absent from our Lord, let us keep our glad hymn for the

day of His return. We are sinners, and have but too often held

fellowship with the world of God's enemies; let us become purified by

repentance, for it is written that 'praise is unseemly in the mouth of

a sinner.'

The leading feature, then, of Septuagesima, is the total suspension of

the Alleluia, which is not to again be heard upon the earth

until the arrival of that happy day, when having suffered death with

our Jesus, and having been buried together with Him, we shall rise

again with Him to a new life.

The sweet hymn of the angels, Gloria in excelsis Deo, which we

have sung every Sunday since the birth of our Saviour in Bethlehem, is

also taken from us; it is only on the feasts of the saints which may by

kept during the week that we shall be allowed to repeat it. The night

Office of the Sunday is to lose also, from now till Easter, its

magnificent Ambrosian hymn, the Te Deum; and at the end of the

holy Sacrifice, the deacon will no longer dismiss the faithful with his

solemn Ite, Missa est, but will simply invite them to continue

their prayers in silence, and bless the Lord, the God of mercy,

who bears with us, notwithstanding all our sins.

After the Gradual of the Mass, instead of the thrice repeated Alleluia,

which prepared our hearts to listen to the voice of God in the holy

Gospel, we hsall hear but a mournful and protracted chant, called, on

that account, the Tract.

That the eye, too, may teach us that the season we are entering on is

one of mourning, the Church will vest her ministers (both on Sundays

and on the days during the week which are not feasts of Saints) in the

sombre purple. Until Ash Wednesday, however, she permits the deacon to

wear his dalmatic, and the subdeacon his tunic; but from that day

forward, they must lay aside these vestments of joy, for Lent will then

have begun and our holy mother will inspire us with the deep spirit of

penance, but suppressing everything of that glad pomp, which she loves

at other seasons, to bring into the sanctuary of her God.

Footnotes:

1 Like Time after Epiphany

and Time after Pentecost, this Season is known as "Ordinary Time" in

the new calendar.

|

|